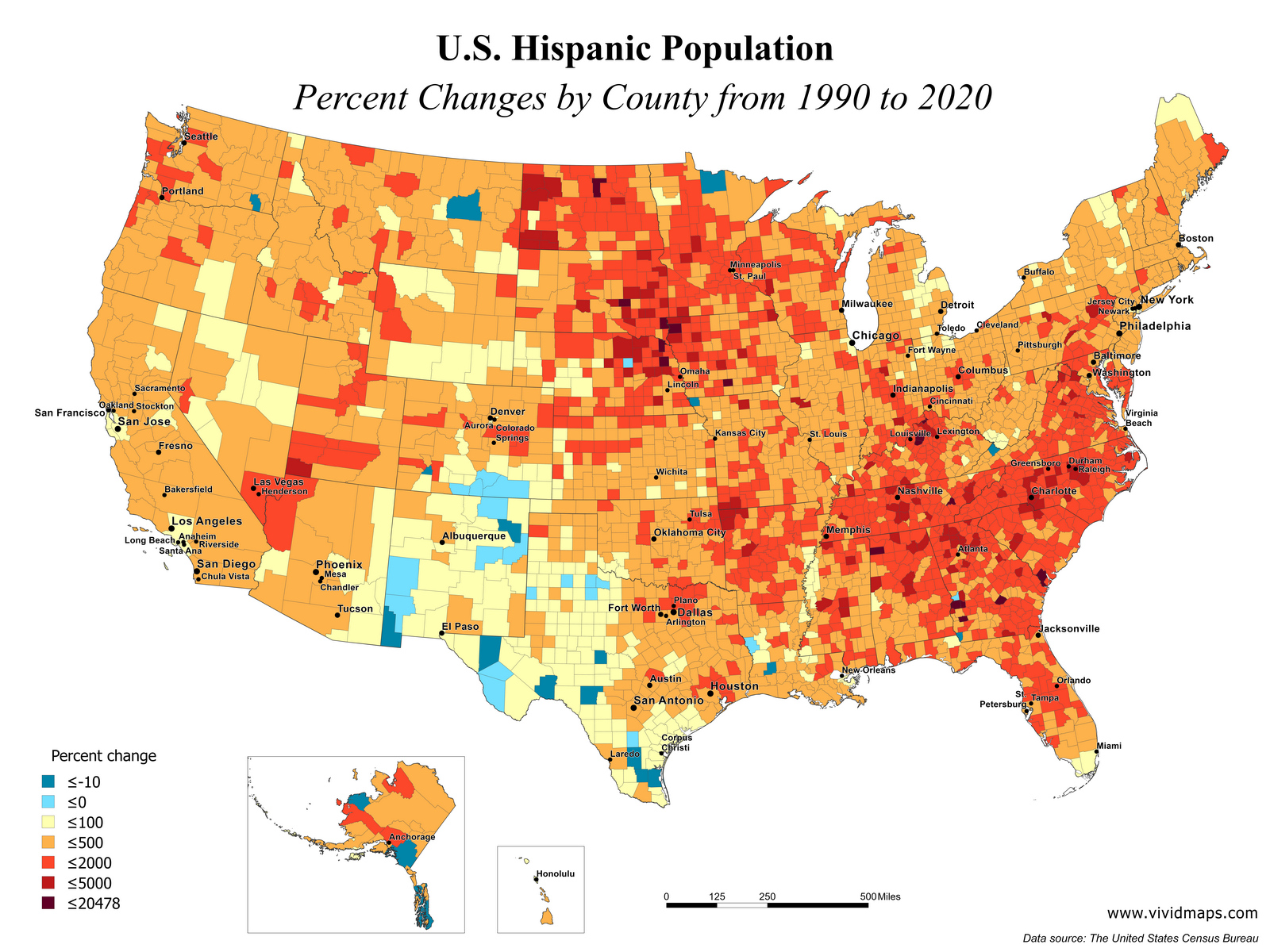

In recent years, few racial or ethnic groups have grown as rapidly as Latinos. Even states that historically have had relatively low Hispanic populations have experienced significant growth in this group.

This new report provides data and analysis on the rapid growth of the Hispanic population. It also examines the ways in which this growth is reshaping communities across the United States.

Demographics

A milestone had long been on the horizon for Latinos: surpassing whites to become the largest population group in Texas. A closely watched Census release last year made it official. Despite the efforts of the Trump administration to add a question about citizenship and to exclude illegal immigrants from participating, the count was not significantly affected by these factors and represented a robust 3% increase since 2010. Hence, the Hispanic population continues to grow steadily, contributing significantly to the cultural diversity and social fabric of many regions around the world.

Mexico led the Hispanic growth (Figure 3-2), but growth among other national groups also occurred. Venezuelans saw the fastest rate of population growth, followed by Colombians, Hondurans, and Guatemalans. These groups are largely the product of new immigration, with many having arrived after 1970, a decade after the first major wave of Latino immigration. The young age distribution of these groups reflects high fertility rates and migration at relatively young ages.

Hispanics now make up nearly one-in-five Americans and have accounted for half of the country’s population growth over the last decade. The vast majority of Latinos are U.S. citizens, reflecting both the naturalization process and the growing number of children born in the United States to Latino parents. The proportion of Hispanics who identify as multiracial has risen sharply, doubling to more than 20 million in 2020. This is likely the result of changes in the census form, which allows individuals to select more than one race.

Employment

The growth of the Hispanic population is reflected in its increasing presence in the employment sector. Hispanics are now a large part of the workforce, and their participation rate has been rising steadily since 1990. During the Great Recession and economic recovery, Hispanics experienced higher job gains than other groups, and their annual earnings were up significantly more than the national average.

But indicators of labor market disadvantage, such as employment gaps or earnings deficits with non-Hispanic whites, persist. These differences are in large part due to relatively low levels of human capital. Hispanics, like other immigrant groups, are disadvantaged in educational achievement, and they tend to acquire work experience more slowly than do other U.S. adults.

In addition, they are more likely to have part-time rather than full-time jobs. Moreover, a considerable share of their working hours is spent in activities that do not contribute to human capital—such as raising children or caring for elderly family members.

These characteristics of Hispanics’ human capital shape their relative success in the labor market. But nativity also plays an important role. As detailed in Chapter 6, the employment rates of Hispanic immigrants are typically 10 percentage points lower than those of the U.S.-born population as a whole, and the gap is much larger for Mexicans. At the more finely tuned level of occupation, foreign-born Hispanics are overrepresented in service and operator/laborer jobs while being underrepresented in managerial/professional and technical/sales occupations.

Education

Hispanics are expanding their presence in states across the country, accounting for a substantial share of population growth in many areas. Their geographic distribution no longer obeys the traditional patterns that characterized earlier European immigrant groups, where networks of social relationships, ethnic enclaves, and niches in labor markets helped to stabilize their settlement.

As a group, Hispanics remain less educated than most Americans and are overrepresented among adults with only a high school diploma or less. But there are signs of progress: enrollment in college is increasing among Hispanics, and there has been a sharp rise in the number of Hispanics who complete a bachelor’s degree.

Nevertheless, college completion rates vary by Hispanic origin group. Some, such as those of South American and Cuban descent, had high levels of college enrollment in 2005 and saw relatively small increases over the next 16 years. In contrast, Mexican and Central American populations began with lower levels of college enrollment and had much larger gains.

Providing educational opportunities to the rapidly growing Hispanic population is a challenge for service agencies. Language barriers, rigorous work schedules, and the need for childcare can make it difficult to provide adult education services that are accessible to Hispanics. However, a focus on meeting the needs and interests of this community could help to bridge these gaps.

Income

Despite the growing strength of the income sector, Latinos still face barriers in their ability to build wealth and pass it on to future generations. They are often paid less than White Americans in the same occupational categories and have limited access to products and services that help them increase their earning capacity or improve their standard of living.

Latino wealth is increasing, but this growth is occurring faster for some than others. For example, households headed by Mexican- and Central American-origin immigrants get over 90 percent of their income from earnings – higher than that for all other Hispanic groups and blacks. This may reflect their strong earning capacities based on education levels and class backgrounds. In subsequent generations, this share declines, perhaps reflecting their growing dependence on other sources of household income.

The 2021 some offers new detailed Hispanic origin variables that allow us to better understand the differences in family net worth among different Hispanic-origin groups. These differences are not reflected in aggregate statistics on the Hispanic population as a whole, which tend to overstate wealth for Latinos compared to other groups. These variables also allow for more precise estimates of the size of remittance pools, and they highlight how remittances have contributed to the rise in Latino wealth. McKinsey’s series of reports on the economic state of Latinos uses these data and other research to explore how remittances have contributed, and continue to contribute, to the growing gap in wealth between Latinos and non-Latinos in the United States.